|

| Russet Burbank Potato, photo courtesy Wikipedia |

My official name is Solanum tuberosum, but you can call me potato. I was born in the Andes of South America, probably near Lake Titicaca on the border of what is now Peru and Bolivia, but some of my ancestors probably came from Chile. My parents were members of the Nightshade family, so that makes me a Solanaceae. Some of my relatives include tomatoes, eggplants, chili peppers and petunias.

|

| Potato plant drawing, photo courtesy University of South Florida |

About 10,000 years ago, the locals began growing me intentionally for food, so that makes me one of the oldest cultivated plants. However, you certainly wouldn’t mistake us for the potato you know today. We were small, multi-colored, bitter, gnarly little nuggets. Different varieties grew well at different elevations, and most villages planted a number of varieties. As a species, we were genetically diverse in our native South America.

|

| Native South American potatoes, photo courtesy Andres Contreras, Universidad Austral de Chile |

The Incas even figured out a way to freeze dry me back in those days. They would spread us out on cold nights to freeze and then thaw during the day. This freezing and thawing turned us into mush. The farmers would squeeze the water out of the mush to make chuño. Chuño would keep for years without refrigeration.

I moved to Europe in the mid 1500s when the conquistadors came to South America in search of gold. They learned to eat chuño, and stocked their ships with it for the long journey home. They also took some of us to plant. We were first planted in the Canary Islands and shipped across Europe during the late 1500s. Sailors had learned that we have great nutritional value and planted us near ports wherever they landed.

When we were introduced to Europe, we were received with apathy, fear and disgust by most of the people. They didn’t understand how you would eat something so ugly. Many believed we were poisonous and caused any number of diseases. Even though we began to be grown throughout Europe, we were essentially a novelty for the gardens of the rich. It stayed that way for the next 150 years. During that time, European countries generally didn’t like each other very much at the time, so there were constant wars. The wars were periodically punctuated by periods of famine. People were hungry.

By the mid-1700s, the wealthy people learned about our nutritional value and began to see us as a solution to the hunger problem. Until then, Europe had relied on grains for food, but traditional practices meant leaving half the fields fallow every year. They learned we could be grown on the fallow fields and not impact grain production. By encouraging people to grow potatoes as a crop, the food supply increased dramatically. Because we are so nutritious and productive, Europe’s food supply almost doubled.

As the food supply increased, so did the population. So, more and more people came to depend on there being more and more food. By the late 1700s and early 1800s, we had become a staple in the European diet. We have three times the caloric value of grains, and we are almost a complete food by ourselves. We only lack calcium, Vitamin A and Vitamin D. So, combine us with milk, and you have the basis of a complete diet. This was especially important in poor areas like Ireland, as many people could be fed inexpensively.

Because we are grown vegetatively, from small pieces of tubers, instead of seed, we became the first agricultural monoculture. Most potatoes grown throughout Europe were genetically very similar, if not the same. This lack of genetic variability set us up for a big problem in the mid-1800s.

During this time, a particular strain of the fungus Phytopthera infestans was developing (probably in Mexico). This fungus is hard on us and causes late blight which can wipe out entire fields. It was beginning to cause problems in the Americas and was transported to Europe in 1844. It spread rapidly throughout Europe. The blight broke out first in Belgium in the summer of 1845 and spread to France by August. It was reported in Ireland the following year.

|

| Potato plants, photo courtesy Wikipedia |

In 1845, 2.1 million acres in Ireland were planted with us. In two months, P. infestans destroyed almost 0.75 million acres, or about one-third, of the crop. The next two years were progressively worse, and the problem didn’t subside until 1852. By that time, a million or more people died in Ireland and two million more left to escape the famine, many to the United States.

In retrospect, this was an early example of the risks of monoculture. Because so many of us were genetically similar, and none of us had any resistance to this fungus, it was able to spread quickly and widely, leaving devastation in its wake.

During the early 1800s, we were gaining popularity in North America as well. We originally arrived in North America in 1621 when the governor of Jamaica sent some of us along with some other vegetables to the governor of the colony of Virginia. The American Gardener’s Calendar, a popular plant catalog of the day, had one potato variety in 1806, but by 1848, it included almost 100 varieties.

|

| Potato flowers, photo courtesy Wikipedia |

At the time, we were mostly grown in New York, Pennsylvania and New England. The late blight infestation that devastated us in Europe was also affecting North America. Much of the attention of plant breeders was focused on developing some resistance to P. infestans.

A young plant entrepreneur in Massachusetts named Luther Burbank chose us as one of his business projects. Through careful selection and breeding and an unbelievable string of good fortune, Burbank developed a variety based on the Early Rose variety that performed particularly well, producing great yields of good tasting, long storing tubers. To finance a move to California, Burbank sold the clone to a New England seedsman for $150. He had wanted $500. But the seedsman named the variety Burbank’s seedling and allowed Burbank to keep 10 tubers, which Burbank used to start his breeding program in California.

|

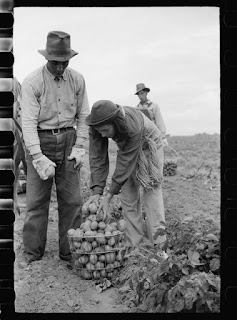

| Harvesting Potatoes in the Rio Grande Valley, Colorado, photo courtesy Library of Congress |

Burbank’s seedling was one of the main varieties planted in the West until a sport, or natural mutation, developed on a plant in Colorado, according to Burbank. Burbank’s seedling produced white tubers, but this sport produced tubers with a brown, almost leathery skin. This new variety became known as the Russet Burbank and is the predominant potato grown in the U.S. today.

For More Information:

Kew Botanical Gardens (http://www.kew.org/science-conservation/plants-fungi/solanum-tuberosum-potato)

After 168 Years, Potato Famine Mystery Solved (http://www.history.com/news/after-168-years-potato-famine-mystery-solved)

How the Potato Changed the World (http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-the-potato-changed-the-world-108470605/)

Luther Burbank: Plant Breeder, Horticulturist, American Hero – Papers presented at the American Society for Horticultural Science (https://hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/pdfs/burbank-workshop.pdf)